I recently saw a petition denouncing Donald Trump that was written by a group of evangelical leaders. The motivation of the quasi-big-shots who signed was to distinguish themselves from an undifferentiated mass of evangelical leaders that (they claim) the media portrays as Trump supporters.

I agreed with every word of their criticism of Trump's candidacy, and I didn't sign the declaration only because in this polarized environment it is likely to be construed as support for Clinton. (I've come out against both.)

But one problem I had with the petition was the signers themselves. A number of them are much too—ahem—generous to themselves when they claim to be evangelicals.

Some signers used to be evangelicals once but now are post-evangelicals or crypto-liberals. Some others may never have been evangelicals at all.

Of course, this begs the question, "What is an evangelical?"

Historian David Bebbington developed an influential four-trait model to answer the question. Other historians have put forth their own lists of characteristics, convictions, or values.

But a complementary way of defining something, in addition to saying what it is, is to say what it isn't. From the beginning, like any movement that makes waves, evangelicals were as remarkable for what they were against as for what they were for. What evangelicals in Germany, Britain, Ireland, and British North America rejected in their first hundred years or so (ca. 1730-1860) still helps us to sort out who is and who isn't an evangelical today.

1. Early evangelicals were anti-scholastic.

I don't mean anti-school or against education—far from it. I'm talking about a fine-grained and inflexible dogmatic theology as the standard of orthodoxy. Such standards were propagated by the University of Wittenberg (Lutheran) at the beginning of the period and Princeton Theological Seminary (Presbyterian) at the end.Evangelicals were not necessarily anti-confessional or anti-creedal, but they challenged the tacit assumption that assenting to a detailed, orthodox confession was evidence of saving faith. Rather, saving faith was the disposition of the heart toward total reliance on Jesus Christ and his cross to be made right with God, evidenced by an "inner witness of the Spirit" and a holy life of benevolent love.

In general, evangelicals held firmly to the doctrinal distinctives of their disparate traditions. But they insisted that those differences did not justify a lack of cooperation among regenerate believers with different convictions.

Many extreme evangelicals—especially later, among the lower class, and on the American frontier—rejected doctrinal formulas of any sort. But all believed that they were insufficient as evidence of true faith and had to be subordinate to the religion of the heart.

2. Early evangelicals were anti-revisionist.

It is misleading to say they were anti-liberal, anti-modern, anti-Enlightenment, anti-intellectual, or anti-scientific. Many deftly integrated liberal ideals, modern philosophy, and scientific methodology into their belief systems.But evangelicals stood against the eagerness in the Enlightenment (and in Romanticism after it) to simplify religion by removing or delegitimizing whatever offended the spirit of the age (which was presumptuously dubbed “reason” or “common sense”).

Evangelicals were inclined (often unconsciously) to use modern methods to find truth in Scripture they had not noticed before, but they refused to declare Scriptural phenomena and teachings fabulous, ingenuine, backward, or irrelevant in the name of reason.

Many extreme evangelicals rejected ivory-tower critical methodology, but all believed that it was insufficient to lead to truth and must be subordinate to the Bible as received.

3. Early evangelicals were anti-formalist.

They were not necessarily anti-liturgical, and they were even less likely to be anti-sacramentalist; indeed, revivalistic campmeetings started out as holy communion festivals.However, a Protestant counterrevolution against both evangelicals and theological liberals in the nineteenth century—especially among Anglicans/Episcopalians but also among Lutherans and Reformed—identified sacraments and traditional liturgical forms as the means of saving grace.

By contrast, evangelicals expected God to work conversion through the individual's engagement with the Bible or in the new liturgical forms of the rural campmeeting and urban "protracted meeting." They demanded that a person testify to receiving grace through one of those channels before admitting them to sacraments. Likewise, evangelicals in traditions that baptized infants considered baptism a hopeful promise, not a saving power.

Many extreme evangelicals rejected anything that smacked of liturgical tradition, but all believed that liturgical, sacramental, and devotional forms were insufficient to bring life and were subordinate to the free movement of the Holy Spirit.

Who isn't an evangelical?

I am not like one of the aforementioned "extreme evangelicals." I often like to explore the area close to the line of confessionalism, modernism, and sacramentalism. Even when I don't get near the line, I find kinship with those who do.But there is a line, and to be on the other side of that line is not to be an evangelical.

So let me break it down for you:

If you contend that ecclesiastically correct or aesthetically rich worship, devotion, or sacrament—ancient or postmodern—is what connects a person to God, you are not an evangelical.

If you contend that biblical teaching that offends modern sensibilities about sexuality, inclusivity, or the nature of truth needs to be overhauled, relativized, or explained away, you are not an evangelical.

And finally, if you contend that adherence to a thorough, precise, orthodox doctrinal confession is what makes an evangelical, you are not an evangelical.

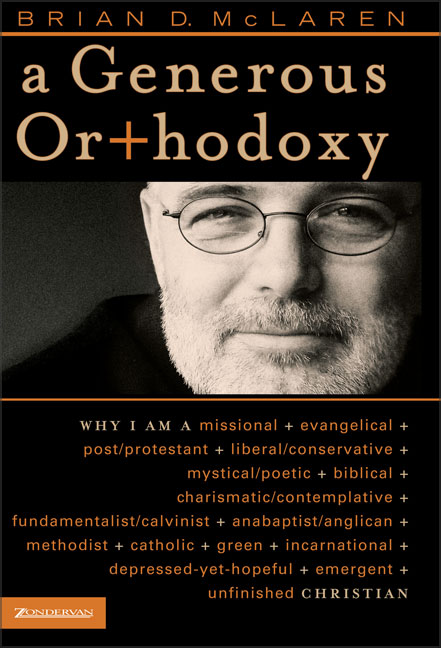

.jpg)

I commend you for your approach. For too long the church has been trained to look only at the things which make us the same. We have been conditioned to ignore those things that separate us. Valid differences need to be recognized because they define the way we look and act and sometimes that makes a world of difference. It takes courage to point out what it is not. (I liked the picture.)

ReplyDelete-- Donna

An insightful commentary that views evangelicalism with a lens that we don't consider as much. Yet there are real differences between evangelicals and those who choose a sacramentalist, revisionist, or purely creedal form of Christianity primarily because evangelicals become deeply concerned with things (especially good things) that remove Christ from the center of our lives and our Christian communities.

ReplyDelete